What is a watershed?

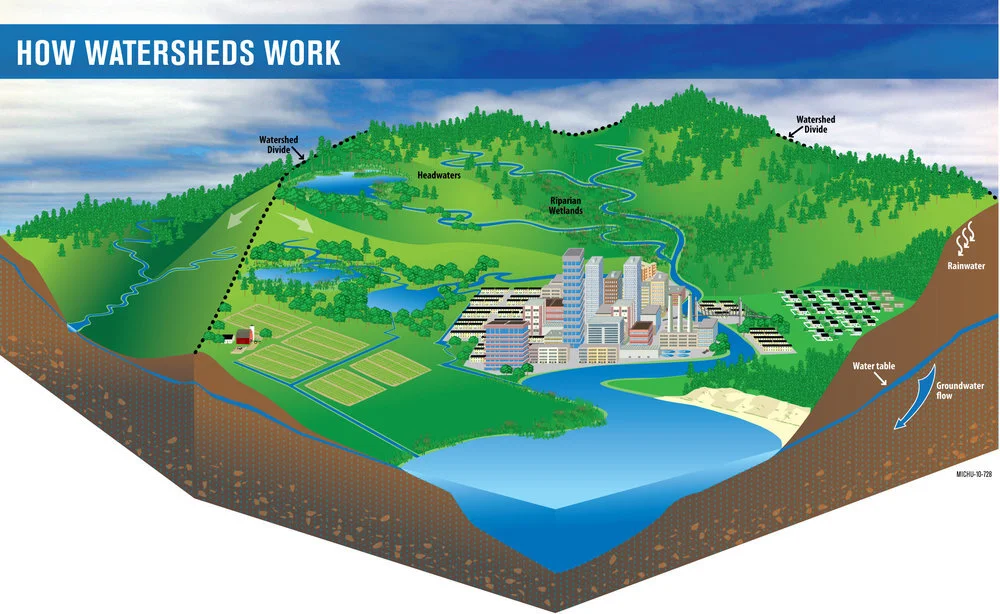

A watershed is an area of land that drains to a common point. When rain falls on an area of land, water that does not soak into the soil or evaporate into the air flows downhill. We often call this water “runoff” or stormwater. The outline of a watershed is defined by high points in the topography, like hills or mountains. Water flows downhill from higher places to a common low point, usually a body of water like a stream or lake.

Often when we talk about a watershed, we focus on surface water, or the water we see on the landscape such as streams, ponds, rivers, lakes and wetlands. But a watershed also includes the groundwater under the surface of the land. In many watersheds, there is quite a bit of interaction between groundwater and surface water. Groundwater feeds streams and rivers during dry periods, and surface water recharges groundwater during wet periods.

On the map of the Lake Thunderbird Watershed, the outline of the watershed is made up of high elevation points. Outside that watershed boundary, rain would flow to a different body of water or low point. Within that boundary, runoff flows toward Lake Thunderbird, often from yards to storm drains, from storm drains through pipes to creeks and from creeks to Lake Thunderbird. You can think of a bathtub as a very simplistic model of a watershed: the rim of the tub is the watershed boundary and the drain is the low point. Any water that falls within the tub’s rim will end up flowing toward the drain.